This course is the advanced follow-up to CS 145, taught by Brad Lushman. Similar to his CS 246E style: dense material, challenging assignments, but incredibly rewarding. The course takes you on a journey from high-level functional programming all the way down to machine code, teaching you how computers actually execute programs.

Course Overview

The central theme is imperative programming and side effects — understanding how programs “do things” that change the state of the world. The course bridges functional programming (from CS 145) with systems-level concepts, covering everything from Racket mutation to assembly language.

Part I: Impurity in Racket

The course begins by introducing side effects to the pure functional world of Racket:

- Mutation fundamentals:

set!,set-box!, mutable structs - I/O modeling: Output as growing character sequences, input as consumption from a stream

- Boxes and pointers: Understanding indirect references and aliasing

- Vectors: Fixed-size, O(1) access data structures

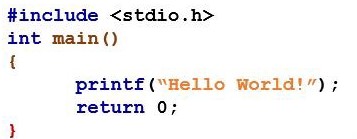

The parallel track introduces C programming:

- Variables, expressions, statements, functions

- Pointers (

*,&), pointer arithmetic - Arrays vs pointers (the confusing rule: array name = pointer to first element)

- Memory layout: code, static, heap, stack

malloc/freeand manual memory management- Linked lists, hash tables implementation

- Common pitfalls: dangling pointers, memory leaks, buffer overflows

Key insight: Racket structs automatically box their fields (pointers), while C requires explicit pointer management.

Part II: SIMPL

Build your own imperative language! SIMPL (Simple Imperative Language) has:

- Variable declarations, assignment, sequencing

- Conditionals (

iif), loops (while), print statements - Arithmetic and boolean expressions

Interpreter in Haskell:

- AST data types for expressions and statements

- State as a map from variables to values

- Adding output via the Mio monad pattern

- Introduction to

>>=(bind) and the IO monad

Hoare Logic for program correctness:

- Triples

{P} statement {Q}— preconditions and postconditions - Rules for assignment, sequencing, conditionals, loops

- Loop invariants for proving

whilecorrectness

Part III: PRIMPL

“SIMPL is all lies” — now we see what programs really look like at a lower level.

PRIMPL (Primitive Imperative Language):

- Programs as vectors of instructions, not trees

- Program Counter (PC) tracks execution position

- No named variables — only memory locations

- Single operations:

add,sub,mul,move,jump,branch - Operands: immediate values

5vs memory references(5)

A-PRIMPL (Assembly PRIMPL):

- Labels, constants, data declarations

- Pseudo-instructions for readability

- Two-pass assembler: build symbol table, then generate code

Compiling SIMPL to A-PRIMPL:

- Stack-based temporary storage with stack pointer (SP)

- Translating

iifandwhileinto jumps and branches - Adding arrays with bounds checking

- Function calls:

jsrinstruction, stack frames, frame pointer (FP) - Tail call optimization

Part IV: MMIX

Donald Knuth’s educational 64-bit RISC architecture:

- Registers: 256 general-purpose ($0-$255), 32 special-purpose

- Memory: 64-bit words, big-endian, byte-addressable

- 2’s complement for signed integers

- Instruction encoding: 32-bit instructions (opcode + operands)

Key instructions:

- Arithmetic:

ADD,SUB,MUL,DIV(remainder inrR) - Comparison:

CMP(returns -1, 0, or 1) - Branches:

BN,BZ,BP,BNN,BNZ,BNP - Memory:

LDO/STO(load/store octabyte) - Control:

JMP,GO(for subroutine calls)

Practical concerns:

- Register allocation and spilling to RAM

- Memory access is slow — registers are fast

- Overflow handling strategies

Part V: Implementing Functional Languages

How does Racket actually work on a real machine?

Data representation:

- Runtime environment maps identifiers to heap locations

- All data tagged with type information

- Cons cells: 3 words (type, first pointer, rest pointer)

- Boxes: 2 words (type, pointer to value)

Shared structure:

- Immutable data allows safe sharing (e.g.,

appendshares the second list) - BST insertion shares unchanged branches

- Only observable through mutation

Closures: Functions capture their environment — can’t use a simple stack model

Garbage collection: Enables safe sharing without manual deallocation

Part VI: Control

Making interpreters efficient and tail-recursive:

Zippers:

- Data structure for efficient traversal: (current focus, context)

- Move forward/backward in O(1)

- For trees: context records descent path and siblings

Continuations:

- Zipper for AST = continuation (“what to do next”)

- Refactoring interpreter to be tail-recursive

interpdescends,applyContascends- Trampolining: bounce function pointers back to a loop

Part VII: Continuations

First-class continuations as a programming construct:

Continuation Passing Style (CPS):

- Pass “the rest of the computation” as an extra parameter

- Every function call becomes tail-recursive

call/cc (call-with-current-continuation):

- Capture current continuation as a first-class value

(let/cc k exp)— Racket’s friendlier form- Invoking

kdiscards remaining computation (non-local exit)

C equivalent: setjmp/longjmp for saving/restoring execution context

Additional C Topics

- Strings: Null-terminated char arrays,

strlen,strcpy,strcmp - Buffer safety:

strncpy, avoidingscanf("%s", ...) - Heterogeneous data:

void *, unions, enums for type tags - 2D arrays: Row-major order, spatial locality matters

- Variadic functions:

va_list,va_argfor variable arguments

Key Takeaways

After this course, you understand:

- Why C has pointers and manual memory management

- How garbage collection works

- What compilers actually do (high-level → assembly → machine code)

- The fundamental difference between functional and imperative paradigms

- How to reason about program correctness with Hoare logic

- The elegance of continuations for control flow

Recommendations

- Take CS 241E instead of CS 241 — this course covers similar compiler content

- The assignments are essential for understanding — don’t skip them

- Draw memory diagrams to understand pointers and aliasing

- Hand-write the interpreters to truly grasp the concepts